Clerks Historical Background on Currency at Settlement Ross

Adapted excerpts from “The Russian-American Company Currency” by Richard A. Pierce (in Russian America: The Forgotten Frontier, edited by Barbara Sweetland Smith and Redmond J. Barnett)

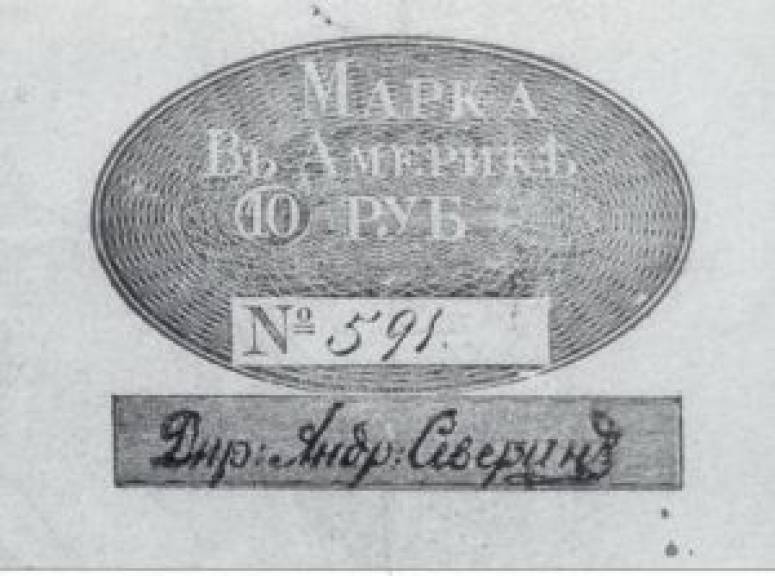

Visitors to the Russian colonies in North America usually remarked on the small pieces of parchment or heavy paper that served as currency. Known officially as marki (singular, marka), or tokens, or assignatsii, but more often referred to familiarly as “skin money” or “leather money” (kozhannye), they were in denominations of twenty-five, ten, five, and one ruble and fifty, twenty-five, and ten kopeks. To help those who could not read distinguish between denominations, some issues were in color — the same pastel tints as had been used for the first Russian paper money issued in the second half of the eighteenth century. Some had holes punched in them or had two or four corners clipped. Most pieces were rectangular; a few were oval in shape. The face of most bore the printed words “Marka v Amerike” (marka in America), the denomination, a hand-written serial number, and the signature of Andrei Severin, a member of the board of directors. The reverse side bore the Russian-American Company seal printed or stamped and the denomination.

The notes were originally of walrus hide used by the Russians to cover packages of furs sent from Sitka to Okhotsk and from there overland and by barge for more than two thousand miles to Kiakhta, the trading center on the Chinese border. There the skin was stripped and again used to cover the chests of tea that were received in exchange for the furs, to protect them for the nearly three-thousand mile trip to Moscow or St. Petersburg. The soundest portions of the hide remaining on the boxes were then cut up and stamped with the denominations, and sent back to the seas. Visitors to the Russian colonies in North America usually remarked on the small pieces of parchment or heavy paper that served as currency. Known officially as marki (singular, marka), or tokens, or assignatsii, but more often referred to familiarly as “skin money” or “leather money” (kozhannye), they were in denominations of twenty-five, ten, five, and one ruble and fifty, twenty-five, and ten kopeks. To help the illiterate distinguish between denominations, some issues were in color — the same pastel tints as had been used for the first Russian paper money issued in the second half of the eighteenth century. Some had holes punched in them or had two or four corners clipped. Most pieces were rectangular; a few were oval in shape. The face of most bore the printed words “Marka v Amerike” (marka in America), the denomination, a hand-written serial number, and the signature of Andrei Severin, a member of the board of directors. The reverse side bore the Russian-American Company seal printed or stamped and the denomination.

From the first years of the Russian-American Company after its founding in 1799, there was a shortage in the colonies of means of exchange. Coins, like all other goods, had to come across Siberia to Okhotsk and then by sea to the colonies, and they were in perpetually short supply. In a secret report to the company board of directors on June 20, 1803, Alexander Baranov, the longtime chief manager, or governor, of the colonies, described the difficulty he was experiencing with receipts, expenditures, purchases, and other transactions because of the lack of coins. This was causing errors in calculation and losses for the company, the promyshlenniki, and indigenous. He therefore proposed that he be supplied means of exchange in either gold, silver, or some other coin as the company preferred, “or some form of obligations on parchment, or various colors.”

In its report to the emperor, the board of directors of the Russian-American Company opposed the idea of sending coins to the colonies. It was still too early, they said, “because the untutored local people, eager for all kinds of metal, can transform coins into finery, and from copper can make spears, arrows and other harmful weapons…” The board eagerly grasped the idea of parchment tokens.

Glossary –

Marka – scrip

Assignatsii – tokens

Kozhannye – skin money or leather money

Bilety – skin money or leather money

Shtempel – company seal

Trade Beads – European explorers and traders introduced glass beads to North America which quickly became highly sought after and embedded into the local trade networks. Trade beads, often made of glass, were small, colorful, and easily transportable, making them ideal for trade purposes. They held significant cultural and symbolic value and were used as a form of currency in exchanges.

Chinese Tea Brick/Tea Money – Centuries ago the inventive Chinese people, who created the earliest banking system with coins and paper bank notes, found their currency had no value when trading with people in far away Mongolia and Tibet. Their solution to this problem was to turn their most valued product, tea, into bricks. The tea bricks were even scored so they could be broken to make change.

The tea “money” manufactured in Southern China is made of leaves and stalks of the tea plant, aromatic herbs and ox blood. It is sometimes bound together with yak dung. Tea is compressed into bricks of various sizes and stamped with a value that varies depending upon the quality of the tea. It usually increases as the bricks circulate farther from the tea producing country. The natives of Siberia prefer tea-money to metallic coins because of lung diseases prevalent in their severe climate, and they regard brick tea not only as a refreshing beverage but also as a medicine against coughs and colds.

The tea bricks could be sold as a whole brick or in parts. You’d take a knife and break or scrape off bits to sell or use. The tea was pressed into neat, ornate bricks to make it easier to handle and to prevent spoilage. Tea stored in buildings or ships had a tendency to spoil if moisture were nearby or if it got wet. This was a way to keep it drier. Most other goods were shipped in barrels, but tea came in chests.

Most of the brick tea was made in China and carried by camel and yak caravans to the distant lands of Tibet, Mongolia and Siberia. Although this tea was used as a form of money during transit, when it reached Russia, it was used as a beverage by the Russian army, tourists, hunters and sportsmen because of its convenient form. For that reason the bricks inscribed in Russian for use there were always of the highest quality and today are the scarcest because they were rarely preserved in their original form.