Brief History and Walking Tour

Read this to your students in the classroom and bring this information with you to Metini / Fort Ross.

Welcome to Fort Ross State Historic Park – The former Russian American Company’s trading outpost in California. The settlement of Ross, the name derived from the word for Russia (Rossiia), was erected on the ancient Kashia Pomo village site, the Metini, in 1812. The founder of the trading outpost was a Russian native from Totma, Ivan Kuskov who came to Alaska in 1790 to spend the next 31 years of his life in North America, assisting his friend and governor of the Russian-American Company, Alexander Baranov in establishing a Russian commercial presence in the New World. Kuskov spent nine years of his North American tenure in California, at the helm of Settlement Ross, directing trade and agricultural production.

The Russians chose the Kashia village of Metini after carefully scouting the California coast for years looking for a perfect spot with a mild climate, rich soil, abundant sea life, and lavish forests to engage in commerce, agriculture, shipbuilding, engineering, missionary activity, and of course sea otter hunting - the most valued trade commodity at the time. To succeed in harvesting the “soft gold”, the Russian forcefully brought with them a group of people from different Alaska Native tribes who were expert marine mammal hunters, a knowledge that was passed down from generations since immemorial. In Alaska, First Nations of the coastal regions around Russian settlements were subjugated and were forced to hunt under the supervision of foremen while their relatives were held hostage. This included half of all males between the ages of 18-50.

The Kashia, an independent tribe speaking one of the Pomo languages, who greeted the Russians and the Alaskan Native peoples had lived along this section of Sonoma Coast for thousands and thousands of years. Bordered by Southern Pomo and Coast Miwok, the Kashia occupied territory stretching 30 miles along the coast and as much as 13 miles inland. As hunters and gatherers, the Kashia moved freely throughout their land, until the arrival of the Russian American Company. In 1812, the Kashia way of life changed forever.

James Allen, whose great-grandmother, a girl of 12, was in the welcoming party at Metini / Fort Ross in the spring of 1812 describes the story of the arrival of the “undersea people”.

“The Russians landed in the harbor. Kids were playing out there, and I guess it was one of my great-grandmothers that saw this ship come in. They didn't know what it was. They never saw one before, this strange thing that came in the harbor.

She ran to the village. It was just right across, back where the fort stands now. "Mother, would you come and take a look?" she said. The mother ran over there and she looked and she said, "Oh, the underwater people have come to visit us!"

They lowered the lifeboats and came ashore, and Captain Kuskov and his crew landed. When he came ashore he reached out to shake hands with, I guess, my great-great-grandmother. Well, by that time the warriors got there.

Shaking hands is not an Indian custom. The menfolk thought that they came to take her away, and that was why he reached out his hand. They were about ready to fill him full of arrows right there. But she, being a great commander and leader who could speak five different Indian languages, said, "No! There's always an argument before an attack."

She just simmered those warriors down, just with that one little phrase.”

The goods, supplies, and materials needed to build a commercial outpost were then taken to land, while the ship was dragged ashore. Afterward, the settlers, comprising of 25 Russians and 80 Alaska Natives, began to labor on the construction of the settlement. By the end of August 1812, the newcomers to Kashia land managed to enclose the site of the fort. The settlement’s official opening ceremony was held on August 30, 1812, (September 11, 1812 Gregorian Calendar) to mark Alexander I name day.

Five years after the founding of the fort, the Russians became the first European nation to officially solidify their presence in the Pacific Northwest through an agreement with the native inhabitants. Formalization of Russian presence in California took place on September 22, 1817, through the so-called Treaty of Hagemeister, signed by Captain-Lieutenant Leonty Hagemeister after meeting Native American chiefs “Chu-gu-an, Amat-tan, Gem-le-le, and others”.

In return for temporarily allowing the Company to use “the land for the fort, buildings, and facilities”, the Russians agreed to render mutual assistance and offer security against the Spanish encroachment from the South, should such necessity arise. The Company also awarded a silver medallion signifying friendship to the elder of the Kashia. The medallion was inscribed ‘Allies of Russia’.

The history of Settlement Ross at Metini is a unique blend of diverse cultural groups. These groups include the Russians, the Kashia Pomo, Coast Miwok and Southern Pomo, Alaska Natives (such as those from Kodiak and the Aleutian Islands), and the Spanish and Mexican settlers. According to the 1821 census the settlement had people from more than a dozen nationalities living at Metini / Fort Ross. The population varied over the years, but never exceeded more than 300 people. In 1836 the trade outpost comprised 260 people - 154 males and 106 females. Out of this number, there were 120 Russians, 51 persons of mixed heritage, 50 Alaska Natives, and 39 California Natives.

The fort that you see in front of you and all the buildings inside it are just a snapshotted fraction of the former size of the Russian American Company establishments at Metini. The settlement had three distinct neighborhoods - the Kashia, Alaska Native, and the Russian centric village. Only the management, and single, Russian heritage employees, lived inside the wooden fortress.

Fort Ross State Historic Park is the only place in continental United States which had an Alaska Native village! Overlooking the bluff, the Alaska Native village consisted of wood and plank houses and possibly some semi-subterranean dwellings that housed single men, families, and mixed households composed of Alaska Native men and California Native women. The Alaska Natives were often referred to as “Aleuts'' but Alaska Natives here were representatives of the Alutiiq, Chugachmiut, Unegkurmiut, Qikertarmiu and Unangan nations.

It’s important to understand that the Alaska Native hunters served as the backbone of the Russian American Company's fur trade. Without these specialized sea mammal hunters, the Russians could never have competed with Anglo and American companies for access to North Pacific furs. Native peoples also provided indispensable foodstuffs to the Russian American Company. Given the tremendous logistical problems of importing food to the North Pacific settlements, the Russians relied extensively on native peoples to provide fresh supplies of locally available foods.

Russian employees of the Company who wanted to start a family in California were allowed to set up private residences and build their own homes in their spare time. Eventually, these private houses grew into a small Russian-looking village just outside the western gates of the fort, called the Sloboda. It consisted of 14 wooden houses as small as 14 feet long by fourteen feet wide and as large as 35 feet by 17.5 feet redwood homes with glazed windows and double planked roofs, each equipped with a private garden. The Sloboda also had eight sheds, eight bathhouses and ten kitchens.

The Russians actively recruited Coast Miwok, Kashia Pomo, and Southern Pomo peoples from nearby coastal communities and interior villages to work at Settlement Ross. The historical native neighborhood north of the stockade was composed of multiple, small, residential compounds. California Native peoples performed a variety of tasks at the settlement - tending livestock, working in the agricultural fields to harvest wheat and barley crops, and hauling clay for brick production. Russian managers noted that a local native population resided near the Ross settlement throughout the year, while others were seasonal laborers used during the peak period of the agricultural season. The California Native workers were paid primarily in kind for their services, receiving food, tobacco, clothing, and other goods.

While relations between natives and settlers were friendly at first, visits to Settlement Ross, especially by men, became rarer and rarer over time. The enmity was a direct consequence of the decision to use California Natives to intensify agricultural production which required tremendous investments of labor to till, sow, cultivate, harvest, and thresh wheat and barley crops. Native workers were often mistreated, working long hours for very little compensation that often consisted of "bad" food. To make matters worse, the Russians mounted armed raids against distant Pomo communities to capture agricultural workers.

Introduction – The settlement of Ross, the name derived from the word for Russia (Rossiia) was established by the Russian-American Company, a commercial hunting and trading company chartered by the tsarist government, with shares held by members of the Tsar’s family, court nobility and high officials. The Company controlled all Russian exploration, trade, and settlement in North America and included permanent outposts in the Kurile Islands, the Aleutian Islands, Alaska, and brief settlements in Hawaii. From 1790 to 1818, Alexander Andreyevich Baranov, the Company’s chief manager, supervised the entire North Pacific area. Trade was vital to Russian outposts in Alaska, where long winters exhausted supplies and the settlements could not grow enough food to support themselves.

Baranov directed his chief deputy, Ivan Alexandrovich Kuskov, to establish a settlement in California as a food source for Alaska and to hunt profitable sea otters. After several reconnaissance missions, Kuskov arrived at Ross in March of 1812 with a party of 25 Russians, many of them craftsmen, and 80 Alaska Natives from Kodiak and the Aleutian Islands. After negotiating with the Kashia Pomo people who inhabited the area, Kuskov began construction of the fort. The carpenters who accompanied Kuskov to Settlement Ross, along with their Alaska Native helpers, had worked on forts in Alaska, and the construction here followed models of the traditional stockade, blockhouses and log buildings found in Siberia and Alaska. Outside the main gate stood the dwellings of the Alaska Natives, brought to the settlement as a labor force, in most cases against their will.

The history of Settlement Ross is a unique blend of diverse cultural groups. These groups include Russians, Kashia Pomo, Coast Miwok, Southern Pomo and Alaska Native peoples, such as those from from Kodiak Island and the Aleutian Islands (Alutiiq), as well as Spanish and Mexican settlers. However, the settlement included a much larger population of Alaska Natives than Russians. The children of Russian and Alaska Native men and Native North American women (persons of mixed heritage), also comprised a large group during the Russian era at Metini / Fort Ross (1812-1842).

On the Trail from the Visitor Center to the Fort – California’s First Windmill – The site of California’s first windmill appears on the 1817 map of Metini / Fort Ross. From this map the windmill is triangulated northwest of the fort on a rise midway between the Northwest Blockhouse, the Visitor Center and Highway One. The windmill is visible on the 1841 watercolor by Russian naturalist and artist, Ilya Gavrilovich Voznesenskii. Two windmills were still there in 1841, with their grindstones, along with an animal powered mill. The original Russian millstones are now inside the fort compound beside the west gate.

The windmills highlight the important agricultural aspect of the Russian American Company settlement at Metini / Fort Ross. One important reason for the establishment of the settlement was to grow wheat and other crops for the Alaskan settlements. The coastal fog, wind, rocky terrain, gophers and lack of trained agriculturalists combined to thwart this effort. Although the Russian American Company established three farms at inland sites between Metini / Fort Ross and Port Rumiantsev (Bodega Bay), and agriculture intensified after sea otter hunting diminished in the early 1820s, production was still insufficient. Trade with Spanish and Mexican California was conducted to increase the food supply to Alaskan settlements, and after 1839 a contract with the Hudson’s Bay Company supplied Russian Alaska with grain and other needed supplies.

On the hill to the north just below the tree line, you can see the Russian orchard. The original Russian orchard encompassed two to three acres, and contained approximately 260 trees at its peak. Fruit trees were planted to provide for the Ross settlement in the early 1800s, and to supplement other agricultural products such as wheat and barley grown in California and shipped to the Russian settlements in Alaska. It has not yet been determined whether the oldest surviving trees date back to the Russian settlement.

Kashia Pomo (The First Inhabitants) – The Native Kashia people have lived at Metini for 12,000 years or more. They have lived on the lands from the Gualala River to Salmon Creek located just north of present day Bodega Bay. The name Kashia, which means “expert gamblers,” was given to them by a neighboring Pomo group. The Kashia, superbly matched to their environment, moved their homes from the ridges in the winter to the ocean shore in the summer, hunting and gathering food from the ocean and the land. Along the shore there were plentiful supplies of abalone, mussel, fish and sea plants. Sea salt was harvested for domestic use as well as for trading. Plants (acorns and seeds) and animals (deer, elk and a vast number of smaller animals) provided abundant food inland. The Kashia created a wide variety of tools, utensils, basketry, and objects of personal adornment which reflected a high degree of technical knowledge, design and artistic ingenuity. Their basketry, a ritual art, has achieved extraordinary respect. The Kashia’s first encounter with Europeans was with the Russians. They provided much of the labor for agricultural efforts at Ross. The high land beyond the highway supported the villages of the Kashia Pomo while they worked at Ross.

The Village Complex (Sloboda) – Most of the Russian American Company population lived outside the fort. Only the higher ranking officials and visitors lived inside. Lower-ranking Company employees and people of mixed heritage lived in the village complex of houses and gardens that gradually developed outside the northwest stockade walls. Intermarriage between Russians and Alaska Natives was commonplace. The children born from these marriages formed a large part of the settlement’s population. Population varied over the years. In 1836 Ioann Veniaminov reported: “Fort Ross contains 260 people: 154 male and 106 female. There are 120 Russians, 51 (Mixed Heritage), 50 Kodiak Aleuts, and 39 baptized Indians.”

Vallejo in 1833 describes the village outside the fort: “The village of the establishment contains 59 large buildings… They are without order or symmetry and are arranged in a confusing and disorienting perspective. Inside the walls there are nine buildings, all of them large and attractive, including the warehouses and granaries.” Later, the inventory for Mr. Sutter in 1841 lists: “twenty-four planked dwellings with glazed windows, a floor and a ceiling; each had a garden. There were eight sheds, eight bath houses and ten kitchens.”

Grinding Stones – These grinding stones up to three feet in diameter and one foot thick were made of indigenous stone. They were once used for grinding flour in California’s first windmills.

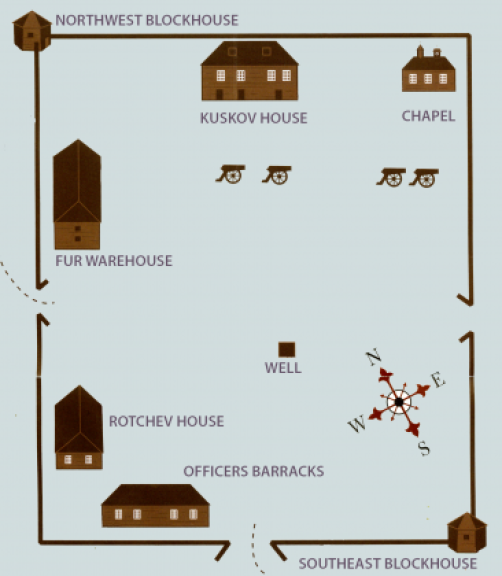

The Fort Compound

Rotchev House - Of the six buildings presently within the fort compound only one, the Rotchev House, is an original Russian-built structure. It is a National Historic Landmark. The Rotchev House is unique and nationally significant because it is one of only four surviving buildings built in the Russian American colonial period, and the only surviving Russian-built structure outside of Alaska. The exterior of the Rotchev House was restored to its late-1830s appearance in a series of modifications between 1925 and 1974. Numerous rare examples of original Russian building techniques are visible. The interior is now the focus of a five-year preservation and furnishing project. The Rotchev House was constructed circa 1836 to serve as the home of Alexander Rotchev, the Russian American Company’s last manager at Ross, his wife Elena, and their children. Alexander Rotchev was an intelligent, well-traveled person and a poet. His wife, Princess Elena, a descendant of the titled nobility, was also accomplished in the arts and conversant in several languages. Accounts indicate that the Rotchev House was considered a relatively refined and properly furnished residence, given its location on the frontier. A French visitor remarked that the Rotchev’s possessed a “choice library, a piano, and a score of Mozart.” The hospitality of the Rotchev’s was highly regarded. They lived in their Ross home until July of 1841.

During the American ranching era following the Russian settlement, the Rotchev House was enlarged with a two story addition and a long front porch by the owner William Benitz. It is possible that the existing fireplace was added at that time. Later, when Fort Ross was part of the George W. Call Ranch, the enlarged structure became the Fort Ross Hotel.

Officials’ Quarters (or Officer’s Barracks) – This building was built before 1817 and was originally the site of company workshops. On the 1817 map it was referred to as “house of planks containing a foundry and workroom for medical aide“. It was refurbished in 1833 to provide Company officials and visitors with accommodations. Reconstruction of the Officials’ Quarters, demolished during the 1916-18 Chapel reconstruction, was completed in 1981.

Southeast Blockhouse – The original blockhouses were built prior to 1817. The southeast blockhouse was reconstructed in a number of phases between 1930 and 1957. Original floorboards from the Officials’ Quarters were used for flooring. This southeast blockhouse has eight sides and offers a clear field of fire, protecting the south and east stockade walls from possible attack. The Spanish were a potential threat to the settlement, and the armaments were always ready, but the defensive value of the fort was never tested. The naval cannons in this blockhouse were used to signal and welcome visiting dignitaries. Historical accounts of the numbers and distribution of the Fort Ross cannons varied over the years. The 1822 the diary of Fr. Mariano Payeras mentions: “…two bastions, one in the northern corner with five guns on two floors, and another on the south with seven guns… Also within the presidio they have four mobile cannons with their gun carriages.” Mariano G. Vallejo in 1833: “12 pieces of artillery on two towers … of 8 caliber, six in each one… All of these pieces are mounted on naval gun carriages except for two “violentos” of 3 caliber…” In 1836 Sir Edward Belcher states “These towers, armed with three guns each… In the center of the yard or square, in front of the governor’s staircase, a brass nine-pounder gun commands the gateway…” 1837 William A. Slacum “…mounts four 12 lb. carronades on each angle, and four 6 lb brass howitzers fronting the principal gate…” 1841 John A Sutter: “From the Russians I have got only one fine brass field piece (mounted with caisson)… This piece has been cast in St. Petersburg, 1804.”

The four cannons now in the center of the fort compound are contemporary reproductions; two are capable of firing. They are 5 ½ inch howitzers mounted on field carriages. In the southeast blockhouse there are 12 pound carronades on naval carriages, as well as a [two?] reproduction 4 pounder bronze Russian cannon[s].

Stockade Walls – The original stockade walls and sally ports deteriorated rapidly. They were reconstructed several times on a piecemeal basis between 1929 and 1989. After Highway One was rerouted to bypass the Fort in 1972, the stockade was finally re-enclosed for the first time since the 1800s. The original walls of the fort were approximately 1204 feet long (172 Russian sazhens) and 14 feet high (2 sazhens). They were held together by a complex system of mortised joints locked by wooden pins. The top truss and the sills were locked into main posts spaced about 12 feet apart extending about 6 feet into the ground.

Chapel – The Chapel was originally built August 1824. It was the first Russian Orthodox structure in North America outside of Alaska, although Ross had no resident priest. The chapel was probably built by the settlement’s shipbuilders. In 1836, Father Ioann Veniaminov, who later became Bishop of Alaska and then Senior Bishop of the Russian Empire, visited the settlement and conducted sacraments of marriage, baptisms, and other religious services. Father Veniaminov had been an active missionary among the Alaska Native people. Unlike the Spanish, the Russian priests in North America baptized only those natives who demonstrated a knowledge and sincere acceptance of Christian belief. The chapel is constructed from wooden boards… It has a small belfry and is rather plain; its entire interior decoration consists of two icons in silver rizas. The chapel at Fort Ross receives almost no income from its members or from those Russians who are occasional visitors. Journal of Father Ioann Veniaminov, 1836. The chapel was partially destroyed in the 1906 earthquake. The foundation crumbled and the walls were ruined; only the roof and two towers remained intact. Between 1916 and 1918, the Chapel was rebuilt using timbers from both the Officials’ Quarters and the Warehouse. On October 5, 1970 the restored Russian chapel was entirely destroyed in an accidental fire. It was reconstructed in 1973. Following Russian Orthodox tradition, some lumber from the burned building was used. The chapel bell melted in the fire, and was recast in Belgium using a rubbing and metal from the original Russian bell. On the bell is a small inscription in Church Slavonic which reads “Heavenly King, receive all, who glorify Him.” Along the lower edge another inscription reads, “Cast at the foundry of Michael Makar Stukolkin, master founder and merchant at the city of St. Petersburg.”

According to Russian Orthodox tradition, the cross on the chapel cupola has a short bar on the top representing a sign nailed to the cross: “Jesus of Nazareth-King of the Jews”; the middle bar represents Christ’s crucifixion; the bottom bar, to which Christ’s feet were nailed, points toward heaven (signifying the thief on the right who repented) and downward (signifying the disposition of the mocking thief). In 1925, the Chapel began to be used for Orthodox religious services, and it continues to be used for such services every Memorial Day and Fourth of July.

Kuskov House – The Kuskov House was the residence of Ivan Alexandrovich Kuskov, who founded Ross and was the first manager. It served as the manager’s house from before 1817 until 1838. In the upstairs were living quarters, downstairs an armory. Four of the Fort’s five managers lived here. First hand accounts describe its historic use: The first room we entered was the armory, containing many muskets, ranged in neat order; hence we passed into the chief room of the house, which is used as a dining room & in which all business is transacted. It was comfortably, though not elegantly furnished, and the walls were adorned with engravings of Nicholas I, Duke Constantine, &c… An (anonymous) Bostonian’s description, 1832. The old house for the commandant, two stories, built of beams, 8 toises[sazhens] long by 6 wide, covered with double planking. There are 6 rooms and a kitchen. Inventory for Mr. Sutter, 1841. The Kuskov House reconstruction was completed in 1983, based in part on the plan of 1817.

The Voznesenskii Room is in the upstairs of the Kuskov House on the northeast corner. Among the later visitors to Ross was the naturalist and artist, Ilya Gavrilovich Voznesenskii. A trained scientist and competent graphic artist, Voznesenskii was sent by the Imperial Academy of Sciences to explore and investigate Russian-America. Many important sketches of the Ross Settlement and its surrounding area come from Voznesenskii’s hand, the result of a year-long visit to Northern California. His avid interest in California’s flora and fauna, as well as native peoples, took him far afield by foot, boat, and horseback. On these and other expeditions, Voznesenskii was able to gather an ethnographically invaluable collection of California Native artifacts.

Northwest Blockhouse – The original was built in 1812. In 1948 ruins of the blockhouse were removed, and it was reconstructed in 1950-1951. The Northwest Blockhouse has seven sides. As a watchtower for sentries with muskets and cannons, it protected the north and west stockade walls from potential attack by land. Each blockhouse carried a flagstaff, used to signal settlements in case of attack or provide a navigational aid for ships approaching Ross. From this blockhouse could be seen the two windmills which were located beyond the fort compound. The three cannon in this blockhouse are of unknown provenance.

Warehouse or Russian Magazin – This two-story Russian-American Company warehouse, or magazin, functioned both as a company store and as a warehouse where supplies for agricultural operations and hunting were documented, assessed and stored for distribution. Reconstruction of this warehouse was conducted by California State Parks. Goods stored in the warehouse reflected extensive Russian trade with Spanish and later Mexican California, as well as Britain, the United States, Europe and China. The Pacific Coast as far north as the northern boundary of the current state of Washington was claimed by the Spanish, though in 1812 they had no settlement north of the Presidio of San Francisco. The Governor of Spanish Alta California, Jose Joaquin de Grillage, was friendly with the Russians, and profited by trade. After his death, the Spanish took a harder line, demanding the removal of the Settlement Ross. While trade with the Russians was strictly forbidden by Madrid, the Spanish settlers found ways to get around the rules, and trade between Settlement Ross and the Spanish settlements continued. Eager to buy goods made by the Russians, the Spanish traded food, which was sent to the Alaskan settlements. When Mexico separated from Spain in 1821, trade with Ross assumed greater importance as the Russians provided military goods to the former Spanish settlement, which no longer had a mother country to supply it.

Well – Archaeological excavations indicate that the original well cribbing was 34 feet deep. Though there was a nearby creek, the well inside the fort compound offered security in case of attack. The site for the settlement of Fort Ross was partially selected because of the proximity of water. The site was also chosen because of nearby timber for construction, the flat coastal terrace surrounding it on which to grow crops, and because it was a defensible site with inaccessible ridges protecting the rear, and a small defensible harbor below.

Outside the Fort –

Alaska Native Village Site – Outside the main gate of the fort stood the dwellings of Alaska Native people who were forcefully brought to the settlement by the Russian American Company to hunt sea mammals and provide a work force for the settlement. The Alaska Native village site was the primary residential area for single Alaska Native men, Alaska Native families, and interethnic households composed of Alaska Native men and local California Native women. The village was situated on the marine terrace directly south of the stockade walls. The extensive archaeological deposit sits on approximately one-half acre, and was investigated by archaeologists from State Parks and University of California, Berkeley, in the summers of 1989, 1991, and 1992. Alaska Natives brought their native baidarkas, swift maneuverable kayaks, used for hunting and transport. From these baidarkas they hunted the valuable sea otter and other sea mammals along the California coast and from a base on the Farallon Islands. Hunted by the Spanish, English, Americans and Russians the number of sea otters was greatly diminished by the early 1820s. The Russian-American Company made the first efforts at marine conservation in the North Pacific when they established moratoriums on fur seal and sea otter hunting. In 1834 the Company stopped the harvest of sea otters for 12 years, and then imposed a strict yearly limit.

Sandy Beach Cove – Sandy Beach Cove lies below the fort. The principal port of the settlement remained 19 miles to the south at Port Rumiantsev (Bodega Bay). There was frequent travel and transport of goods between Sandy Beach Cove and Port Rumiantsev in Russian launches and Alaska Native baidarkas (kayaks) and baidaras (large, open skin boats used to carry cargo and up to 15 passengers).

In the cove area below the settlement were a number of buildings including a shed for the baidarkas, a forge and blacksmith shop, tannery, cooperage and a public bath. There was a boat shop and shipways for building ships. Farm implements and boats were sold and traded to the Spanish, and four Russian-American Company ships—three brigs and a schooner—were the first built on the California coast. The shipyard was abandoned by 1825, but smaller boats continued to be built.

The Russian Cemetery – Across the gulch to the east Russian Orthodox crosses mark the site of the settlement’s cemetery. Over 150 people were buried in the cemetery during the Russian-American Company’s thirty-year settlement here.

“To the northeast at a cannon shot’s distance they have their cemetery, although unfenced. In it there is a noteworthy distinction… [a] mausoleum atop a sepulcher of three square steps, from larger to smaller. Above these was a pyramid two yards high, and over it a ball topped off by a cross, all painted white and black, which is what most attracts one’s attention when you descend from the mountain. Over another burial… they placed only something like a box, and over the Kodiaks a cross… All of the crosses we saw are patriarchal; a small cross above and a larger cross nearby like arms, and below, a diagonally placed stick…” Payeras, 1822.

In 1990 the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee assisted the California State Parks in a project intended to better understand the boundaries and composition of the historic Russian cemetery. Excavations to locate and identify the individual Orthodox burials were conducted. The names of individuals associated with specific burials are not known, although researchers have identified a lengthy list of people who died at Settlement Ross and were most likely buried here. The Ross settlement was a mercantile village with many families, and there are a large number of women and children buried in the cemetery. Remains have been re-interred and given last rites by priests of the Russian Orthodox Church. Artifacts, such as beads, buttons, cloth fragments, crosses and religious medals found in the cemetery restoration project, will help researchers better understand the Russian settlement’s culture.

Adapted from A Guided Walk at Fort Ross State Historic Park excerpt – published by Fort Ross Interpretive Association – 2004.